On Networks and Mind Control (my research interests #6)

My current research journey in 2024 and beyond, ft. rather questionable aspirations

As you may know, my research studies the temporal development of ideas in network mediums, using graph theory. Here I offer a brief history, some concepts to help us stay on the same page, and my weird fascinations going forward.

My Research History

Over the summer of 2024, I started researching datasets of news articles under a sensitive project. I deduced the dependencies of the articles on each other using time and natural language similarities. With some magic network analysis, I ultimately tracked down a [redacted] by flagging a pattern of anomalous relationships.

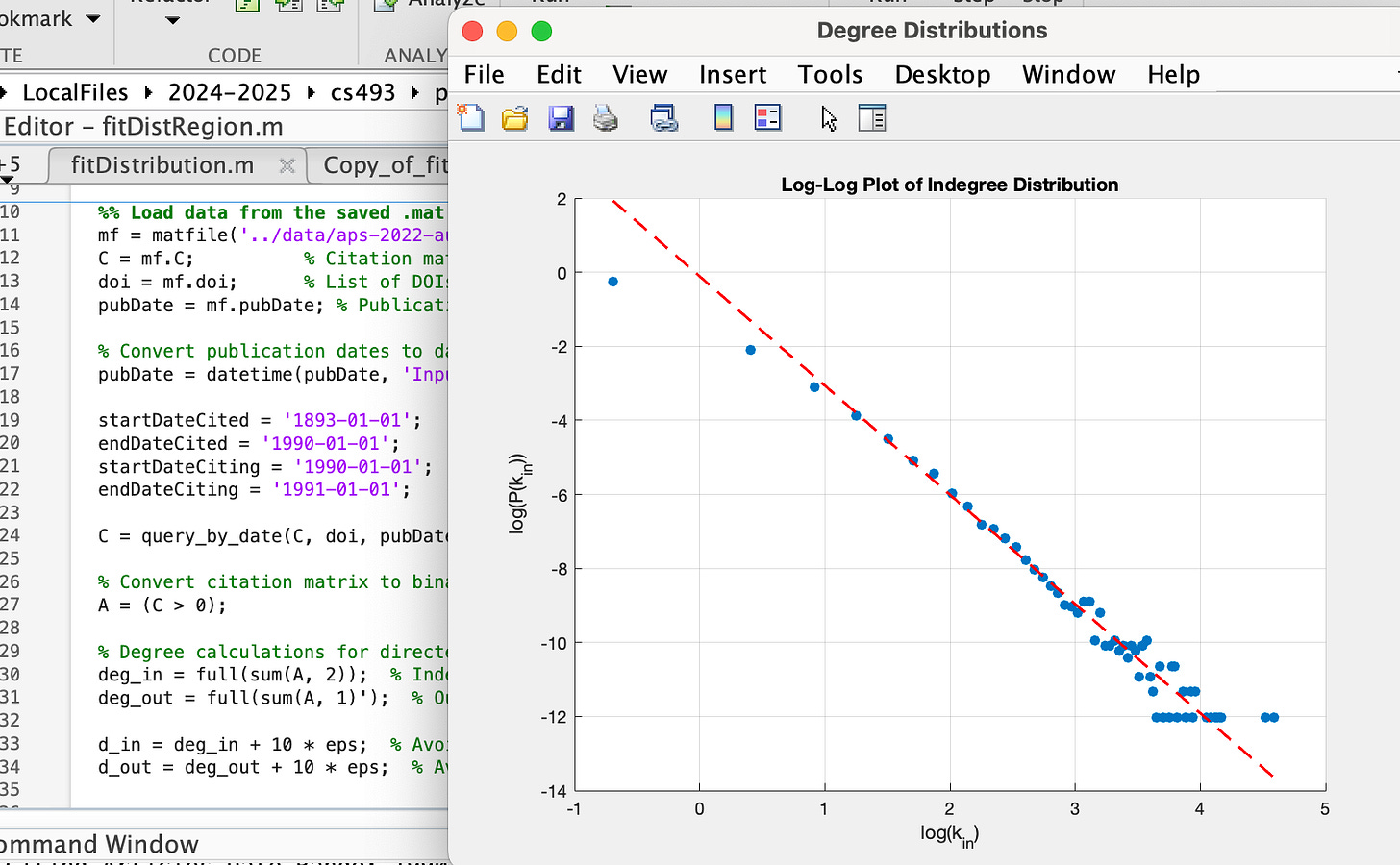

In the Fall, I turned to datasets of academic journal articles. Here, the dependencies between publications are made obvious through citations, leaving us with a cleaner, time-directed acyclic graph. This makes it easier to quantify a baseline for how time-varying networks behave, which is the first step in more precise anomaly detection!

The two insights from my research I would like to eventually discuss are (1) the large academic citation network comprises a mixture of subcommunities of articles and (2) there is a tipping point in the virality patterns of the most successful ideas. Let’s go!

Real-World Networks: The Rich-Get-Richer Effect, and Something More

To begin, note that the formation of real-world networks usually entails a preferential attachment, or “rich-get-richer” mechanism. Think of how popular Instagram influencers show up on more peoples’ feeds, and thus accumulate followers faster; or the growing concentration of wealth among society’s top 1%. In the same way, preferential attachment leads to some form of inequality in the prevalence of scientific publications, too. These particular patterns of inequality are collectively called scale-free behaviours.

Of course, a model trying to simulate a citation network needs more than just a preferential attachment mechanism. Perhaps some ideas are successful because they’re just “better” than others (think Einstein’s theories of relativity), and some are better-placed in time and space (think Ronald Burt’s theory of structural holes, and how Delay, Deny, Defend flew off the shelves because Luigi took the shot.) These circumstantial factors result in citation networks looking slightly different from even what state of the art models predict.

To pay lip service to the central finding of my Fall collaboration, we found evidence for a previously undocumented circumstantial factor: subcommunity mixing. See, the theory of preferential attachment suggests that to observe scale-free behaviours, it is essential for the dataset to have a growth component; that is, a dataset of academic publications must stretch back to the very earliest papers of the journal. However, we observed that a) when we considered just one highly-cited paper and its descendants, the paper’s community of descendants also displayed scale-free behaviours; and b) the whole dataset, including the journal’s earliest papers, deviated in small but consistent ways from textbook scale-free behaviours.

Accordingly, we proposed that i) a single seminal work gives birth to a new academic subfield (shown as a subgraph); ii) preferential attachment mechanics apply within these subcommunities, rather than homogeneously across the dataset; and iii) these offer a novel explanation from the small and consistent deviations observed in (b).1

The Life-Cycle of an Idea: “Gaining Immortality”, and Why

While this finding is mathematically interesting, I was personally even more interested in the second, which involves what happens when we zoom in on an idea that is much more “successful” than others.

First, consider that most ideas have lifetimes. After their emergence, they sometimes garner some spike of attention, but almost all eventually fade. But not all. At some point in this natural life cycle, a paper occasionally “catches fire” (or induces a cascade, technically speaking). This means it draws the attention of other research groups and fields, and becomes cited more and more, even at an increasing rate over time. Papers like this are often anomalies that evade the predictions of any one model.2

Now this interests me greatly. Why, or when, do some ideas “explode” into something of far greater and more lasting impact?

People may be Machines, but Control is Not So Simple

For a long time, I’ve struggled with a strange paradox. Repressive institutions, be it governments or family traditions, rarely produce neutral outcomes. If they don’t succeed in prolonging their control, they are brought down by the rather violent rebellion of their subjects; there is no in-between. For example, Singapore’s government has over six decades manufactured a national mindset of remarkable homogeneity,3 while Christian tiger moms, praying hard as they are for their children to be filled with the Holy Spirit, are losing ground real fast.

I’d like to understand what makes– or breaks– the inculcation of an idea in a person. Whether it’s “Don’t Smoke”, “Don’t Spend”, or “Give your life to Jesus”, what makes an idea take root?

Three words come back to me from my D.C. stint in political campaigns: persuasion, turnout, and virality. If most people take to the idea, it has succeeded in persuading. If most people change their behaviour because of the idea, it has turned them out. If most people repeat the idea, it has succeeded in virality. Let’s suppose the “success” of an idea can be measured along these axes.

Whether it’s “Don’t Smoke”, “Don’t Spend”, or “Give your life to Jesus”, what makes an idea take root?

Math-y interlude notwithstanding, I honestly suspect that formulas can only take us so far when we go back to the central question. Highly structured institutions have risen and fallen for millenia, and me + math aren’t going to crack a puzzle that’s eluded humans for all of recorded history. And yet, I believe that there are significant factors out there that help us be better understood by others, such as showing others that we really care to understand them, too.4

If you could instill an idea in a whole population, what would it be?

Six years ago, I would not recognize my ideals today. was at the height of my Christian institutionalism era. I fancied things like theocracy (where God is directly involved in the state) and thought God had tasked me to instill my Christian ideals of discipline and emotional conviction on a massive scale. (Where do you think my desire to work in a national government first came from?)

Today, I cringe at much of the church’s rhetoric, from war-imagery in the realm of politics to intensely emotional experiences that involve some combination of joy and guilt. The present David now values empathy and open-mindedness, which in many circumstances conflict with the above.

Will I be recognisable by the time I make it to where I need to be to effect change?5

Furthering this investigation might have yielded more, exciting findings about the growth, persistence, decay and death of these subcommunities, among other behaviours in the dataset.

Incidentally, it has been found that citation network datasets that contain a greater fraction of such “hot” ideas deviate all the more from what we can model. (Source: The Transition Towards Immortality: Non-linear Autocatalytic Growth of Citations to Scientific Papers by Golosovsky and Solomon).

For more on the society-building efforts of the Singapore government, stay tuned for another article.

How deeply would such an understanding have to go? Given how deep and complex a person is, perhaps it is a job that can only be handled by our subconscious, as I wrote about in MIM #5.

For more on how I perceive environment to shape me, stay tuned for another article.